Last Monday, the Transportation Authority of Marin (TAM) released $20.2 million in funds for planning and construction of road projects around the county [1]. The funds come from Measure A and Measure AA, a pair of sales tax measures with funding dedicated to transportation. If you were to only read the strategy document for Measure AA [2] and TAM’s Strategic Vision Plan [3], you would guess they’d go predominantly to road repairs and strengthening the bike and transit networks in Marin. You’d guess wrong.

Here are the three big-ticket items.

Sir Francis Drake

TAM has wanted to reconfigure Sir Francis Drake Boulevard from Ross to Highway 101 for years. Along this stretch, lanes are weird, sometimes as wide as 16 feet, and the sidewalks are narrow or nonexistent. During commute hours, the intersections along the route are quite congested, around Level of Service E or F, and bike access along the corridor is nonexistent.

The plan is to add a third lane southbound by narrowing the existing lanes, widen the sidewalks, remove the dangerous slip lanes at various corners, repaint some crosswalks, and do a bunch of miscellaneous pipe and streetlight work for a total of $22.9 million. All of this is good, but there is plenty of bad.

First, there isn’t accommodation for protected bike infrastructure anywhere along the route. TAM’s planner for the project told me it was due to the preponderance of driveways, especially in Kentfield, but that isn’t a good answer given the lack of driveways on the north side of Drake from Wolfe Grade to 101. Putting a two-way protected bike lane on the north side of Drake has its own problems, but there wasn’t even an attempt.

Second, there are a bunch of three-legged crosswalks, where people on foot can cross between three of the four pairs of corners, like so:

By my count, every major intersection has this problem. These mean that someone getting off a bus and needing to reach the diagonal corner will need to wait through 2 light cycles rather than 1, exposing them to more traffic, fumes, and delaying their trip for up to 2 minutes. Given that a typical rush-hour driver is delayed just 3 minutes today [4], it seems foolish to delay people on foot by a similar amount of time for want of some paint.

The project was awarded $11.9 million.

Novato Boulevard

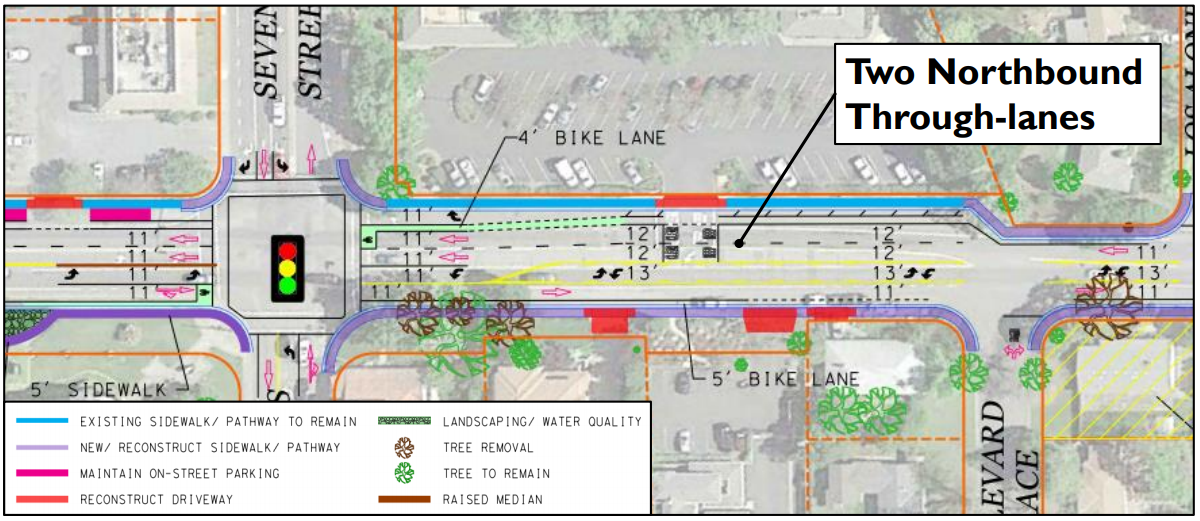

Novato wants to redesign its self-titled boulevard to accommodate more traffic, estimating that the road will decline from level of service B (no traffic ever) to level of service C (heavy traffic at rush hour but no delays) level of service D (heavy traffic with mild delays) to level of service F (stop-and-go) by 2043 [5]. As recently as 2014, the road was operating with no delays (level of service B) [6], so the fast decline in service could simply be temporary or easily diverted. Rather than go with the 5-lane alternative, which would have actually widened the already-bloated road and destroyed six houses, Novato has chosen a 3-lane alternative, which still takes some property but doesn’t add capacity to the street. While better than the 5-lane version, this remains a bad plan.

Image from the City of Novato.

I looked at Novato Boulevard as an example of an obese street a few years back [7]. Novato Boulevard has no traffic problems today and actually has capacity to spare. But instead of looking at future level-of-service, I came up with a proposal to right-size the street: eliminate the center turn lane, narrow the traffic lanes to 10 feet, widen the sidewalks and planting strips, and, of course, add protected bike infrastructure. Novato’s preferred plan does none of that, instead keeping 5-foot wide painted bike lanes (which are absolutely inappropriate on a major road) and a 13-foot-wide center turn lane – wider than a freeway lane. And remember, it’s extremely rare for this street to have any traffic whatsoever.

Somehow, this pointless project got another $1 million.

Highway 101 to I-580 Connector

One of the perennial headaches of Marin’s freeway system is going from northbound 101 to eastbound 580. Right now, drivers need to exit 101 onto a surface street – Bellam – before merging back onto 580, causing rush-hour backups. Caltrans and TAM want to fix this by building a new interchange, at a cost of up to $265 million, to allow drivers to stay on the freeway.

There are two problems with this approach. The first is that TAM staff showed back in early 2016 that the intersection with Bellam can be upgraded to a level of service C – meaning you’ll need to wait just one light cycle – and eliminate the backup onto 101 entirely with a small widening and reconfiguration [8]. It’s not necessary to build a whole new interchange or ramp.

The second issue is that if the goal is to ease commuters going between the East Bay and southern Marin (or vice versa), the real slowdowns happen elsewhere. In Marin, it’s at Westbound 580 to southbound 101, which involves a much more complicated route through surface streets, a transfer that the ramp project wouldn’t ease. In the East Bay, the westbound backup approaching the bridge’s toll plaza regularly stretches back for three miles and take up to 40 minutes to get through. Helping this would mean switching to electronic toll collection, not a new ramp in Marin.

In short, TAM is putting $6 million towards an essentially useless quarter-billion-dollar project. On the plus side, it will do little to promote driving given that it’ll do so little to speed driving. But Marin has other priorities that need funding, and $6 million can buy a lot of protected bike infrastructure.

What about environmentalism?

These projects are all about driving and cars, but Marin’s transportation problems are all about bikes, transit, and carpooling. The county’s priorities should be:

Make Marin County a world-class biking county, rivalling The Netherlands in bike safety and access.

Make buses faster, with bus-only lanes from Santa Rosa to the SF Transit Center, working with SCTA and SFMTA to make it happen through the neighboring counties.

Make buses cheaper, cutting regional fares by at least 20 percent and funding free transfers between the agencies Golden Gate Transit operates around.

Listening to TAM, they talk a good game about environmentalism and multimodalism. I doubt any of its board members or planning staff would argue that the climate is changing or that humans are to blame. But if we are to judge character based on actions rather than words, TAM has shown itself to be just as unconcerned about climate change as a coal baron. Each of these projects further entrenches car culture and driving into the collective consciousness of Marin, shirking our responsibility as environmentalists to “act local” in stopping the destruction of our planet.

An old adage is, “Where your money is, there your heart will be also.” If so, then Marin’s heart is asphalt and oil.

Works Cited

[1] Will Houston, ‘Marin Transportation Agency Allocates $20M for Projects’, Marin Independent Journal, 9 July 2019.

[2] Transportation Authority of Marin, ‘Transportation Sales Tax Measure AA Strategic Plan’ (San Rafael, CA: Transportation Authority of Marin, 30 May 2019).

[3] Transportation Authority of Marin, ‘Getting Around Marin: Strategic Vision Plan’, Draft (San Rafael, CA: Transportation Authority of Marin, 2017).

[4] LSA, ‘CEQA Environmental Impact Report: Sir Francis Drake Boulevard Rehabilitation Project’ (Point Richmond, CA: Transportation Authority of Marin, March 2018).

[5] City of Novato, ‘Novato Boulevard Improvements’ (Novato, CA: City of Novato, June 12, 2018).

[6] City of Novato, “Existing Conditions Report” (Novato, CA: City of Novato, April 1, 2014).

[7] Edmondson, David. ‘What to Do with a Road That’s Too Wide.’ The Greater Marin, December 12, 2017.

[8] Transportation Authority of Marin, ‘Access Routes from US‐101 to the Richmond San Rafael Bridge’ (28 January 2016).

Header Image: Popov, Alexander. Car, Transportation, Vehicle and Automobile. Digital Photograph. unsplash. Accessed 17 July 2019.