Last Thursday, TAM released a cautiously optimistic report (PDF) on implementing bike sharing in Marin. The preliminary report’s caution is well-warranted, as the county’s infrastructure and urban form are far different from bike share pioneers Paris and Washington, DC. If Marin can thread the needle and create a quality bike share program, it could be a pioneer for other suburbs.

Last Thursday, TAM released a cautiously optimistic report (PDF) on implementing bike sharing in Marin. The preliminary report’s caution is well-warranted, as the county’s infrastructure and urban form are far different from bike share pioneers Paris and Washington, DC. If Marin can thread the needle and create a quality bike share program, it could be a pioneer for other suburbs.

Introduction to bike share

Bike share, the system examined by TAM, is a bicycle rental/transit hybrid. Bikes are stored in stations, like the one pictured at right, which are scattered through the area. Users purchase a membership for a certain amount of time, usually just a day, week, month, or year. While a member, users can pick up a bike from any station and drop it off at any other station. If done within a certain time, like 30 minutes, the trip is free. If the trip goes over that time limit, a fee is levied for every subsequent half-hour.

The point isn’t to check out a bike for a round-trip but rather for each short leg of a short journey. Want to get from downtown MillValley to Whole Foods? Check out a bike, ride it to Whole Foods, dock it there and do your shopping. After you’re done, check out another bike from the station and ride it back downtown or wherever you want to go next.

I’ve been a member of the Washington, DC, system for most of the time it’s been active. Capital Bikeshare, or CaBi, is used by tourists to get between museums on the National Mall, commuters to get to work, revelers to get around after the Metro system closes, and for general trips around town. I’ve used it for all those purposes and it works great for all of them.

The key is to have bicycles and docks always available at a given station, and to have stations conveniently located. There’s nothing worse than arriving at a station to find the bikes are all gone or to find there’s nowhere to dock your bike, especially if there’s nowhere nearby that does have a bike or dock.

The company contracted to operate the system will “rebalance” the bikes from one station to the other. In DC, the operator pays a fee if any station is empty or full for more than two hours. Users know where bikes, docks, and stations are by looking at screens on the stations or with a smartphone app.

The Marin system

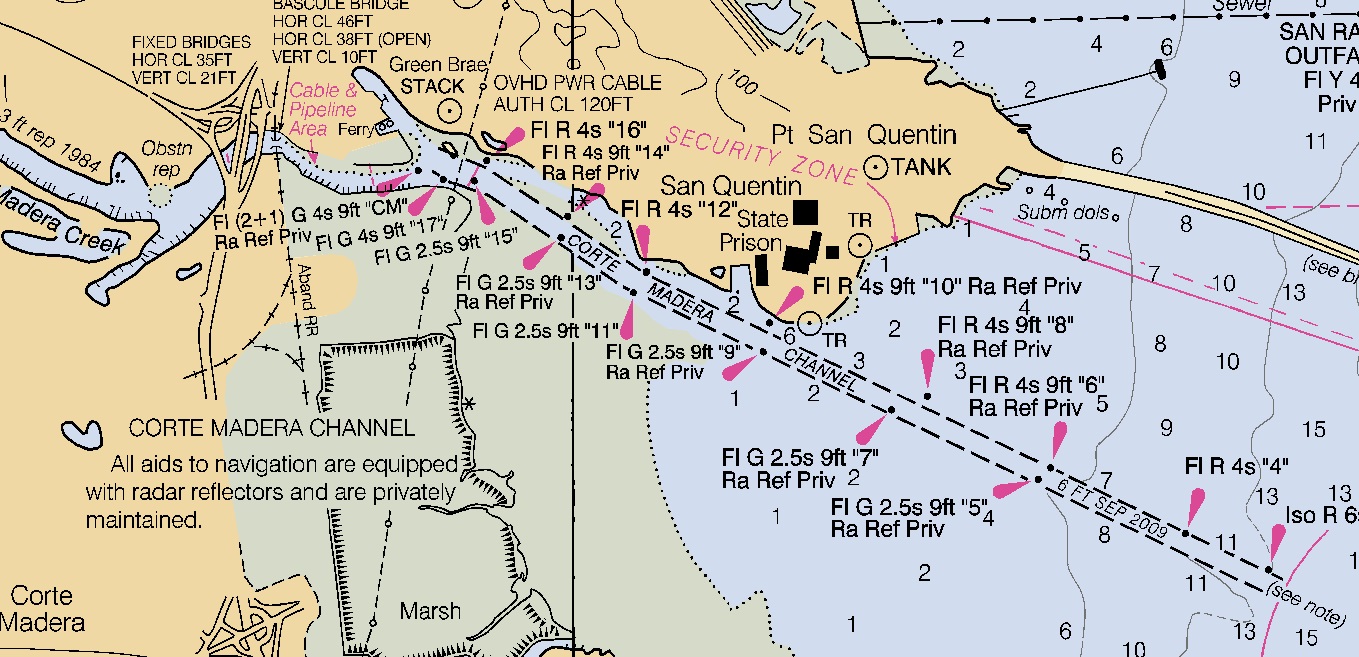

TAM wants a bike share system to serve primarily the commuting public, to solve what transit planners call the Last Mile Problem. When a rider hops off a bus, they’re at a location that might a ways away from their final destination. To get to the final destination, riders typically walk, though bikes are a common sight on Marin’s bus fleet. With bike share, a rider doesn’t need to bring their own bike.

With that in mind, the first stations would be focused on moving people from downtowns to ferry terminals and transit centers. Twelve stations, one in most of the downtowns and one at the two ferry terminals, would provide a way to get commuters around the county. Subsequent phases would make more stations around activity centers, which would make the system more like CaBi.

Total cost would be around $720,000 for the first phase and $2.2 million for full build-out.

Obstacles

A major barrier to the success of the bike share system will be the paucity of quality bike facilities between downtowns and activity centers. Though it is possible to ride through most of Marin, it isn’t always pleasant, and the safest route is sometimes far out of the way.

Between most downtown pairs lies a few miles of bike-hostile arterial roads. Though most have safer parallel routes, those parallel routes don’t access the businesses that grew up along the arterial. Since bike share is a utility rather than leisure system, the separation of businesses and bike routes diminishes just how much utility bikers can get from the system. Given how low density Marin’s origins and destinations already are, the last thing we need is to diminish separate bikes from businesses.

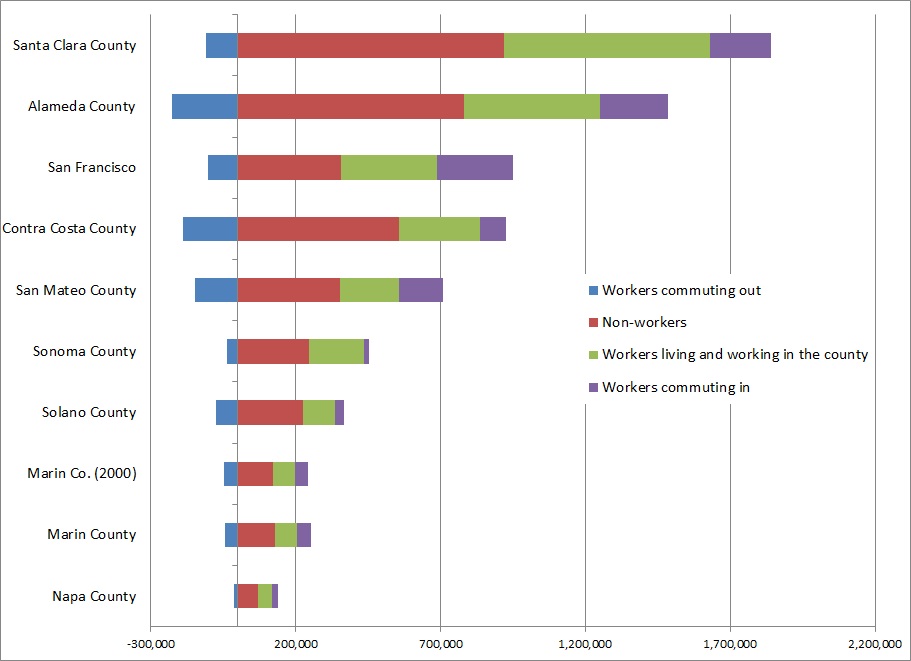

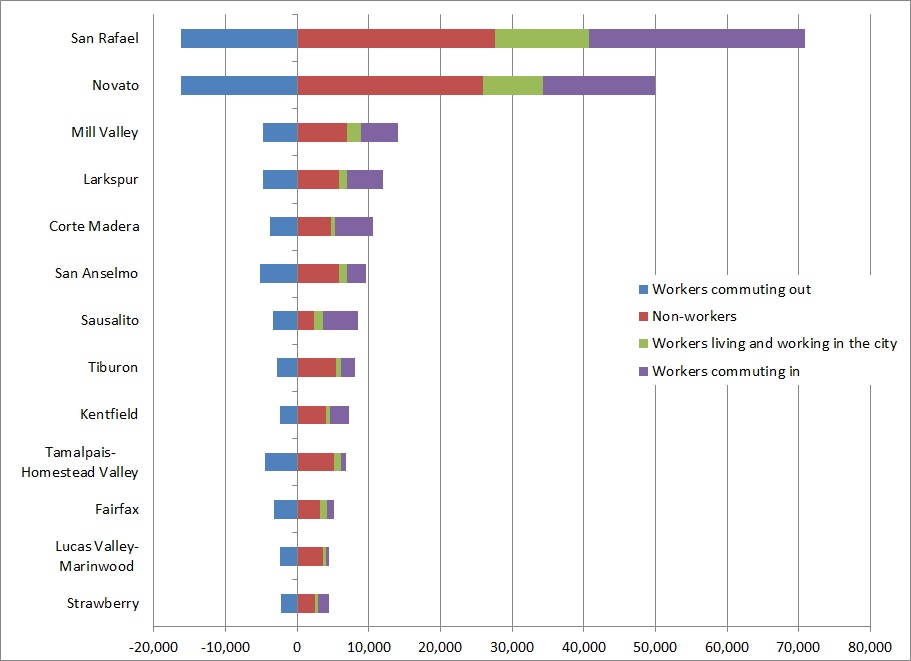

Marin’s demographics are another potential obstacle. The foundation of most bike share systems is the 25-34 age group. Though they’ve been growing in Marin, the group is a fraction of the size it is in DC or San Francisco. Planners want to harness the 35-45 age group instead, though they’ve been reticent about adopting bike share elsewhere.

Opportunities

The bike share report seems to underestimate the power of tourists in Marin. Particularly in Sausalito, a major driver of use will be tourists. DC’s system was never designed for tourists, but once the system opened on the National Mall the bikes became ubiquitous. Sausalito already gets thousands of tourists. If Marin’s system is integrated with San Francisco’s quite delayed plan, I suspect a huge number of tourists and day trippers will use bike share to hang out around Sausalito and Tiburon. As well, commuters to the City will be able to use their bike share membership at home and for their commute, taking away some of the demand for bike space on ferries and buses.

Bike share is its own best advertiser. Once a small system is up and running, demand springs up elsewhere. People, even transit-savvy New Yorkers, often don’t understand what bike share does before it’s active, but once it is people know it and love it. Richmond, Novato, and maybe even the closer-in West Marin villages like Bolinas and Stinson will want in on the action.

As a nifty indirect effect, bike share puts people in touch with the infrastructure in their communities. A street looks different from a bike. What feels like a narrow lane behind a windshield can feel like a broad avenue on a bike, and what feels slow in a car feels fast to a biker. Advocacy for better bicycling facilities can come from a well-used bike share system.

Oddities

The report isn't without its problems. The draft plan doesn’t adjust the projected level of usage over time which, frankly, doesn’t make sense. People will use the system more as more stations become available and as people get used to the idea of bike share. It looks like they copied the final station proximity numbers into Phase 1 and Phase 2 but kept the introductory usage numbers for each phase. It would be good to get that sorted out.

The first phase includes only one station in Novato, a small loner in the middle of downtown more than an hour from the next nearest station. Though it is census area with the most bike commuters in the county (6.1 percent!), it doesn't make sense to add only one station. Riders who arrive and find the station full will be stranded in the middle of nowhere with the clock ticking on their bike. Stations in Tiburon and Mill Valley are similarly isolated.

There are missed opportunities for new stations in San Anselmo and Mill Valley. In San Anselmo, the commercial centers along Center, namely Yolanda Station and Lansdale Station, should be quality sites for infill. Miller Avenue at La Goma and Tam High should score higher as places for expansion.

It is a true shame that College of Marin doesn't get a station until Phase 2. Young people form the core of any bike share program. Leaving out a major destination for them until later in the program is foolish in the extreme. One of the more isolated stations - Novato or Tiburon - should be placed there instead.

National context

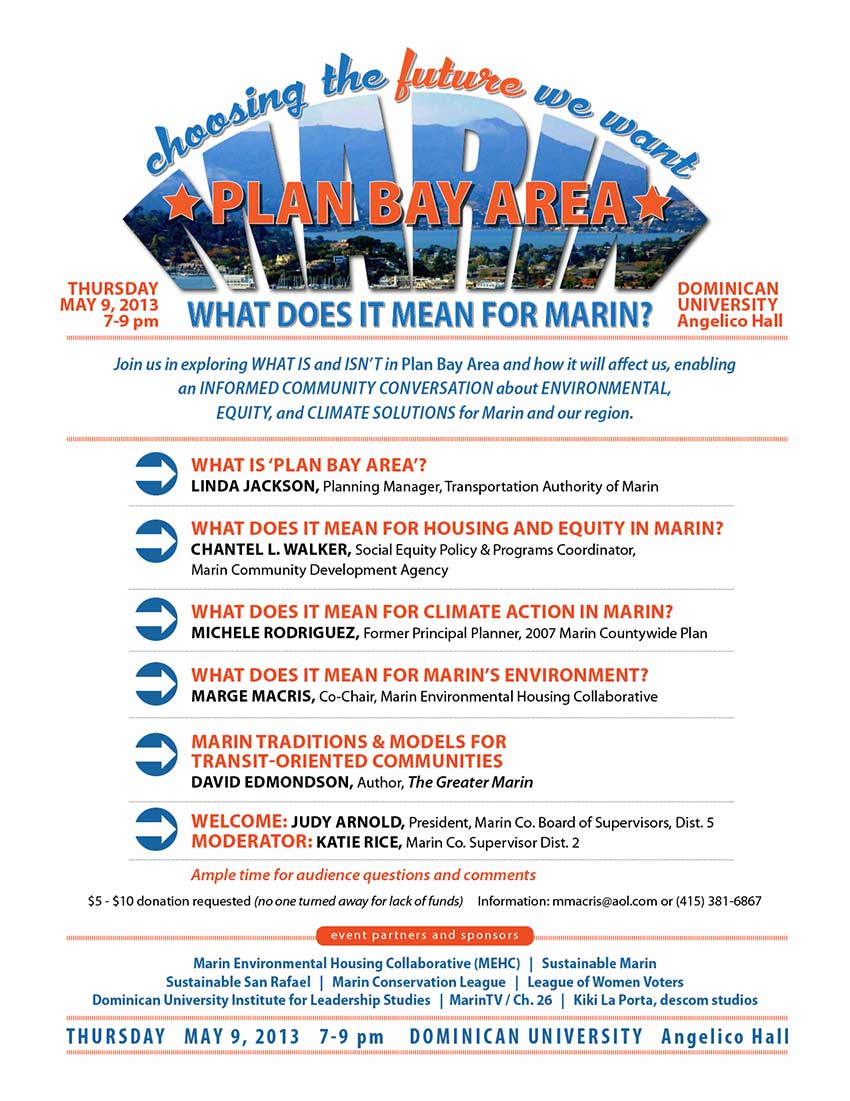

Bike share is sweeping the nation. It is transforming cities across the country and will soon reach the Bay Area. Marin should not get swept up in the trends for their own sake, and I’m glad the county is proceeding with caution. The next phase of planning is another baby step – $25,000 to find sponsors and study the potential subscriber base, which will put more flesh on the report’s bones.

If Marin’s system does pan out, it will mean bike share is far more flexible than the high-density systems that launched the wave. That means suburbs like Marin, from Surrey, BC, to Staten Island, NY, will have an example of a functional system to hold up as an example. The good news for Marin, then, would mean good news for the country.