One Bay Area, the organization behind Plan Bay Area, surveyed the region's opinions on the built environment. What kinds of transportation investments do we want? What kinds of cities do we want to live in? What would get you to take transit or ride a bike more? Though the survey has problems, it gives us the most comprehensive look at the Bay Area's support for urbanism.

Last time, we looked at Marin's support for regionalism. (There was a lively discussion on this post's Patch incarnation.) Though there was was strong support for the underlying assumptions around Plan Bay Area, Marinites were far more divided on these issues than any other county in the region. A large minority was strongly negative about any regional planning. Today, we examine Marin's perspectives on the specific policies that shape Plan Bay Area. As a reminder to readers critical of Plan Bay Area, this will not address the underlying policy successes or failures of Plan Bay Area, only the opinions of its assumptions and how local and regional plans match those opinions.

Survey responses

The survey asked people three questions about development policy. The first was about funding priorities, and it began, "Next I will read you a number of items that may be considered as part of this Bay Area plan. For each, please tell me whether whether funding should be a high priority or not a priority. Use a 5-point scale where 5 means 'High Priority' and 1 means 'Not a priority.'"

After a number of questions about transportation, the survey asked about the policy, "Provide financial incentives to cities to build more multi-unit housing near public transit."

The next questions were about support for policies, and they began, "Next I will read you a list of specific strategies being considered to reduce driving and greenhouse gases. Indicate whether you would support or oppose each using the same 5-point scale."

The two policies were, "Build more housing near public transit designed for residents who want to drive less," and, "Limit urban sprawl by requiring most additional housing and commercial buildings be built within current city or town limits."

On all three Marinites answered more negatively than the region as a whole, and neither opponents nor proponents make up a majority of opinion on any of the questions.

The first asks a question nearly mimics the rhetoric of development skeptics, and so is probably the best measure of their influence in the county. In response to the question of whether the region should provide subsidies to cities to build more multi-unit housing near transit, Marinites were deeply divided. Though 39.9 percent were in favor, fully 30.8 percent were opposed, with 28.9 percent in the middle. This is the most opposition to the program in the region, which was otherwise 51.2 percent in favor and 20.9 percent opposed. The standard deviation, a measure of disagreement, was 9 percent higher than the rest of the region, too.

On the second question, Marin again bucks the region, though not nearly as much. On the question of whether you support building more housing near transit for those who want to drive less, Marinites were 59.7 percent supportive and 20 percent opposed, versus 65.4 percent and 12.1 percent, respectively, for the rest of the region. We also had nearly twice as many people answer that they were strongly opposed than moderately opposed: 9.5 percent versus 5.3 percent.

On the final policy question, whether development should be limited to only areas within existing city limits, Marin again answers more negatively than the region as a whole, though here it has company. A strong minority, 31.2 percent, opposes this policy, the most in the region. Joining it are Contra Costa (29.7 percent) and Santa Clara (28.2 percent). This question also trigged a very strong negative response, with 18.7 percent reporting that they are strongly opposed. Intriguingly, Marin’s support lines up with the rest of the region exactly: 41.6 percent of the region and the county support this policy.

I did not expect this last result. Marin’s urban growth boundaries are a cherished part of our civic lore, as the continuing success of Rebels with a Cause shows. Indeed, this is so unlikely I suspect the problem lies with the question.

“Limit urban sprawl” may have been interpreted as razing the suburbs, a fear I’ve heard in community meetings and read in online comments. The question also talks about additional housing and commercial buildings, which suggests new growth. The strong negative reaction may have been more against any new housing and commercial buildings, not just those outside of existing municipal boundaries. In any case, there is too much wiggle room in how one could understand the question to glean much useful information from it.

These responses reflect Marinites’ opinions about what makes a good home and a good town. A plurality thinks high-density transit-oriented development would ruin our town character (41.7 percent vs. 36.9 percent). A similar plurality would not move to a more densely-populated area to live near amenities (42.3 percent vs. 38.8 percent). On these questions, Marin is more strongly negative than any other county in the region.

How does our planning stack up?

Keep in mind that, although each of the policies addressed in the above questions has stronger opposition than anywhere else, they each have plurality or majority support. Even subsidized housing, which has the weakest support, has a 9 point advantage over the opposition. Where opponents find strongest ground is in home preferences. A plurality believes high-density development would ruin town character, and a plurality wouldn’t trade higher densities for more amenities. Combine the two measures (give people choice to drive less but don’t increase density) and you get a no-change, slow-growth status quo, which is what planners have largely given Marin in the past few decades.

Plan Bay Area, which encourages localities to focus growth by pledging to focus planning and transit funding, does not fit this status quo. While most of Marin got by on its RHNA mandates by pledging to zone for housing growth, very little of it was actually built in part because of a lack of investment from host cities. Focusing investment could mean real changes.

This is best seen in the eastern half of the Civic Center Station Area Plan. Planners and proponents wanted to focus growth into an area that would, they hope, give people a choice to use the car less. But, for some residents, four- and five-story buildings where now there are parking lots means living in a higher-density area at least some are trying to avoid.

The flip side is also true. While Marinites favor giving people a choice to live car-free or car-lite lifestyles, there is little support in city or county plans. In downtown San Rafael, Marin's urban core, new developments are subject to parking minimums, tight density limits, and inconsistent floor-area ratios. These restrictions discourage developers from creating apartments designed for those who choose to live car-free or car-lite. For example, a proposal for for-profit apartments by Monahan at 2nd & B streets was 10-20 units smaller than it could have been without those restrictions.

The Downtown SMART Station Area Plan gets closer to lifting these restrictions by eliminating density limits in favor of a hard height limit, but planners left parking minimums in place. Renters, whether car-free or not, will need to pay for a space in their building. Developers will need to dedicate floor space to parking instead of rent-paying uses, like apartments or retail.

The debate itself

They survey also begins to shine some light on the structure of Marin's development debate.

Rhetorically, opponents’ language (“high-density San Francisco-style stack-and-pack housing”) is ideally suited to play on Marinites’ general distaste for density. As well, the policy environment, with its focus on RHNA mandates and affordable housing, keeps the conversation on a policy with a meager base. Opponents will win as long as they can tie a development policy to RHNA, affordable housing, Plan Bay Area, and the like, forcing proponents to scramble to the defense of relatively unpopular policies.

Yet the broad popularity of subsidized housing and higher densities in the region at large means opponents have an uphill battle if they want to move beyond the development politics that has dogged Marin for the past three years.

I suspect that one reason for deepening divide in this policy area in Marin is that it is just incessant. Just as we start wrapping up one RHNA cycle, Plan Bay Area begins. Just as that is settling down next year, the next RHNA cycle will come about. Marin’s development skeptics rightly feel under siege, as every victory is fleeting.

Proponents, meanwhile, are destined to continue to lose as long as the conversation is about affordable housing and housing units per acre. Unfortunately for them, they’ll get no favors from the regional housing process, which will keep shifting the conversation back to opponents’ favored ground. Instead, proponents need to talk about choice and character. Urbanist lawmakers need to say, “We need to give choices to our young people. We need to give people the option to drive less.”

The right policy package could also cut the legs out from opponents’ ground. A for-profit-friendly zoning code, sold as bringing choice, town character, and less driving could get some easier play in town meetings. If passed, it would bake into the zoning code the growth RHNA asks for, rendering future development debates much less contentious.

The takeaway

If there is a theme to this data, it is that Marin is deeply divided on issues of development. Though, again, there are no areas where Marinites are more against than in favor of a policy, those on the negative end of the spectrum are rather more strongly negative, with more 1s than 2s, than those on the positive side are positive, with more 4s than 5s.

It doesn’t hurt that in the Bay Area as a whole, likely voters are more strongly negative on these issues than unlikely voters. While we don’t have data on Marin’s likely voters, the region’s broader trend seems to reflect what we see in the county: civically engaged and organized opponents against much less visible and seemingly rudderless proponents.

Overall, Marin has played to stereotype so far, at least to some degree. Its residents have strong views on development policy that are both more negative and more divided than those in the rest of the region. Intriguingly, this includes the rest of the North Bay: both Sonoma and Napa are more positive than Marin on development policy.

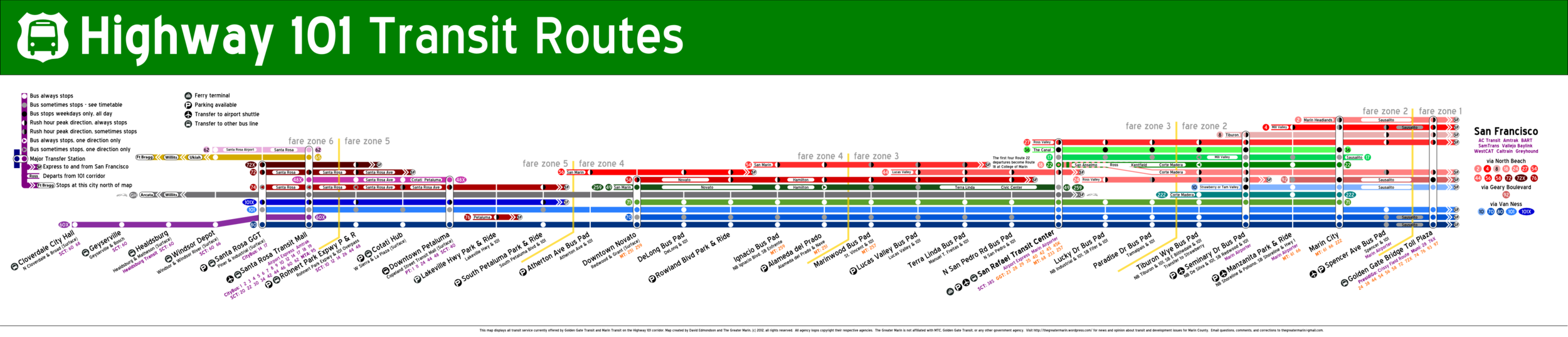

Of course, land use policy is only one side of the planning coin. Transportation policy is intimately linked with development policy, and will be discussed next time.